Art & Culture

About Art & Nature | In Conversation with Ebba Koch

LA 59 |

|

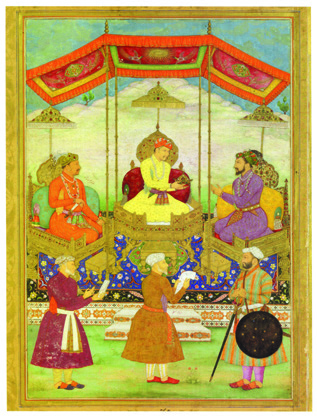

| In Conversation with Ebba Koch about the release of her book, "The Mughal Empire from Jahangir to Shah Jahan: Art, Architecture, Politics, Law and Literature' [2019], which she has compiled and edited with Ali Anooshahr. Here, she discusses differences in approaches towards garden design under the two imperial rulers and much more...

|

|

|

|

The last time we met on the release of your book, 'The Complete Taj Mahal and the Riverfront Gardens of Agra,' we spoke about your involvement in the Taj Mahal Conservation Collaborative [TMCC]. What has been its progress since then?

The Taj Mahal Conservation Collaborative was founded in 2001 as a new initiative for `the conservation and restoration of the Taj Mahal and surrounding areas and a new site visitor management' in a partnership between the Indian government, represented by the Archaeological Survey of India, and the private sector, the Indian Hotels Company Ltd., that is the Tata Group of Hotels. The Taj Mahal Conservation Collaborative was directed by the conservation architect Rahul Mehrotra [now professor at the Harvard School of Design] and advised by a body of Indian and foreign experts which included myself as an architectural advisor. As part of the initiative a new Site Management Plan for the Taj Mahal complex and its precincts, sympathetic to tourism, was being worked out, and a new Visitors Centre was established. Upon my suggestion it was integrated in two of the ruined outer courtyards of the Taj Mahal complex, originally intended as living quarters of the care takers of the tomb, which were restored true to their original form for this purpose. However, the Visitors Centre still awaits opening.

About 'The Mughal Empire from Jahangir to Shah Jahan: Art, Architecture, Politics, Law and Literature' [2019]

How did the landscape perspectives differ in the reign of the two rulers in India? How did the socio-economic contexts shape these perspectives?

The conventional opinion of garden and landscape historians holds that the foremost characterization of the Mughal garden, introduced into India under Babur, is its emphasis on architecture and orderly planning. It has further been suggested that the Mughals saw in their strictly planned and consistently furnished charbagh as a means to demonstrate the new order of Mughal rule in Hindustan [Asher 1991; Wescoat 1992]. The Mughal variant of the Persianate charbagh [in the strictest sense of the word, a cross axial fourfold garden] became a module in the planning of cities and palaces, and in the last analysis, under Shah Jahan, a political metaphor of a golden age, brought about by the good government of the Great Mughal. But a closer look at the Persian sources and surviving evidence led me to suggest that inthe past, discussion on Mughal formalism has been somewhat overstressed and that the connection between chaharbagh and Mughal imperial order in India has been argued too narrowly. The geometrical aspects of the Mughal garden have diverted our attention from another approach, especially adopted by Jahangir, where no regular system is forced upon nature but where nature is the protagonist. Here, the natural landscape is the determining factor, or a feature of nature becomes a garden element in itself. The Mughal padshah claims nature as his own by making a permanent imprint on it with artistic means. The natural form, highlighted and ennobled by the emperor by architectural frames or inscriptions, plays now the role of a garden element of his realm and, consequently, turns his territories in the widest sense into his garden. It testifies to the deep engagement of the Mughals with India that they expressed themselves here largely in Indian terms. Jahangir had even large freestanding elephant statues hewn out of the living rock on a pass into Kashmir! The wedding of art and nature led under Shah Jahan to the artificial garden, realized with architectural plant forms, such as the cypress shaped baluster column in his palaces. This inspired a floralization of all later Indian architecture, in all types of buildings and in all regions. Thus, what had begun as the most unorthodox of Mughal approaches to landscape had, in the end, the most enduring impact.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|