Theory & Discourse

City| Landscape: A Rumination | Sriganesh Rajendran

LA 56 |

|

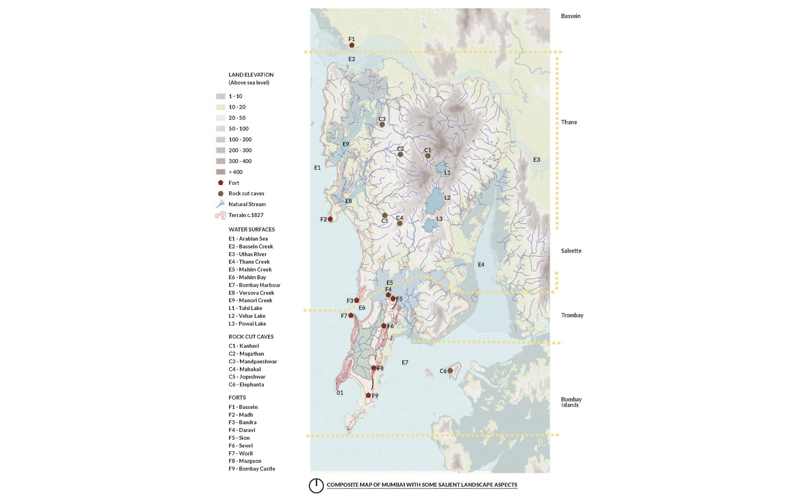

| Regardless of the sea, creeks, streams and a forest core, Mumbai evokes the metaphor of a 'concrete jungle'. To appreciate the city's natural landscape and ecological structure it is essential to look for clues in between its frenetic development. Transects across the city reveal a range of urban patterns and form. They also identify rocky foreshores, sandy beaches, tidal flats, marshlands, creeks and plains from the south to the north. A similar sequence is seen from the Thane creek on the east to the Arabian Sea along the west. The forested hills of Borivali National Park cohesively bind these, creating an intrinsic landscape pattern..

|

|

|

|

Intrinsic landscape

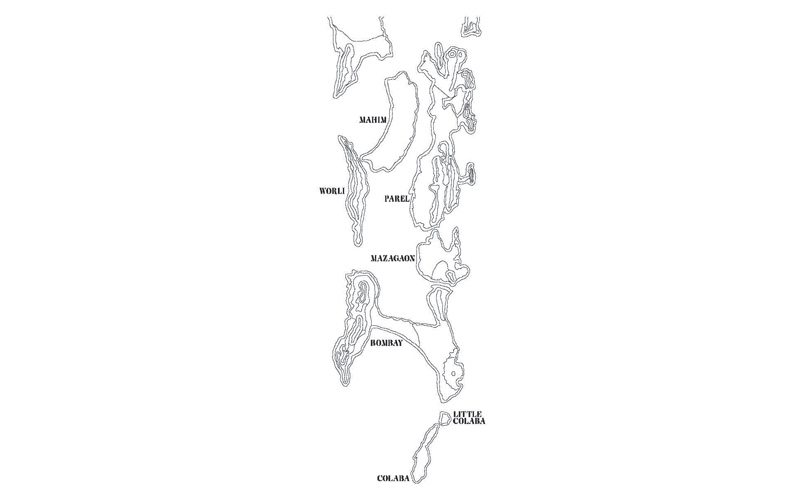

Mumbai's evolution from a natural archipelago to its present amalgamated landform is well known and forms a typical narrative beginning from the reclamation of seven islands. Peeking into prehistory takes us into a landscape that formed roughly 65 million years ago, coeval with the disappearance of dinosaurs. This landscape witnessed the Indian subcontinent's migration towards the Asian plate until 35 million years before present. Thus, a long period of sea level changes, volcanic flows and geochemistry became causal factors in the genesis of a terrain that would be seen by mapmakers from the sixteenth century onwards.

In this terrain, the relative orientation of hills in the 'Bombay islands' and Salsette, Elephanta and Trombay suggest an apparent parallelism. Broadly speaking, the eastern faces of Mumbai's hills exhibit a homogenous and compact structure, while the western sides are more weathered and heterogeneous. This influenced the siting of rock-cut caves at Salsette island (1st century BCE to 9th century CE), and the occurrence of the famed 'Kurla' and 'Malad stone' cladding seen on colonial buildings (mid-eighteenth-nineteenth century CE). The differential cooling of the lava flows created some remarkable features such as Gilbert Hill, Andheri, with its perfect polygonal columnar jointing, nearly 50 m high, while contact with sea water gave rise to 'pillow' shaped rock formations, as seen at Malabar Hill and Haji Ali. Many hillocks in the city retain only a vestigial elevation due to quarrying (e.g. Jari Mari, Hanuman Tekdi, Cumballa Hill etc.). The aforementioned Gilbert Hill-a National Geological Monument-originally covered a greater area; what remains is sandwiched by high-rise buildings.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|