Cities

Urban Designers and Historic Cities | Samuel Noe

The Decline of Traditional Sensibilities

LA 48 |

|

(Orginally published in 'DESIGN- Magazine of Art & Ideas', April- June 1980)

Our perceptions of traditional cities serve as a basis for our approach to preserve them as urban designers. We need to view ourselves as protectors and sympathetic participants in a complex decision making process with many invested stakeholders. We must be responsible for and work towards the enhancement of the existing environmental quality in the city.

|

|

|

|

As urban designers we are more and more concerned about the environment of the traditional city. This growing interest reflects recent architectural fascination with vernacular environments and with preservation of historic structures. But it also expresses a social concern among professionals active in the Third world. For in this environment a majority of the urban population still lives under social and economic conditions in many ways similar to those of much earlier times. Therefore, traditional environments still have a strong relevance, giving validity to our concerns. Yet when our interest be¬comes more than passive, we are faced with significant questions growing out of our personal values and accustomed ways of working. These questions concern our level of understanding of the traditional community, our will¬ingness to accept values and concerns different from our own, our concepts of professionalism, our relationships to clients and employers (and in turn their relationships to the community), and finally the nature of our profes¬sional education.

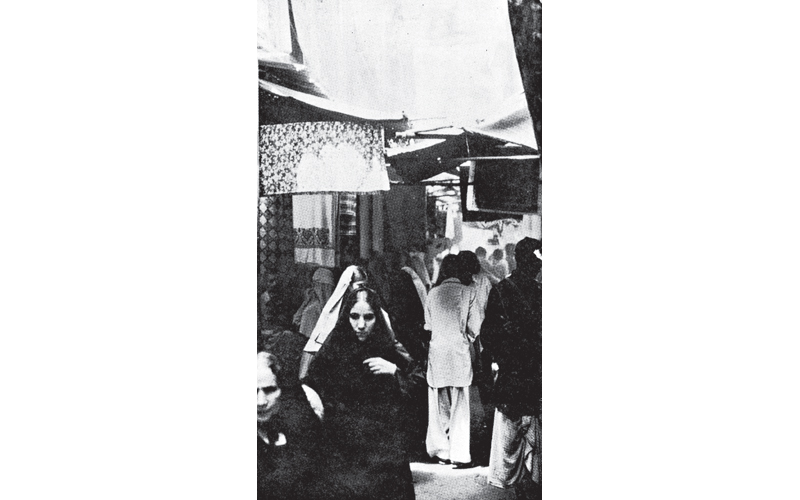

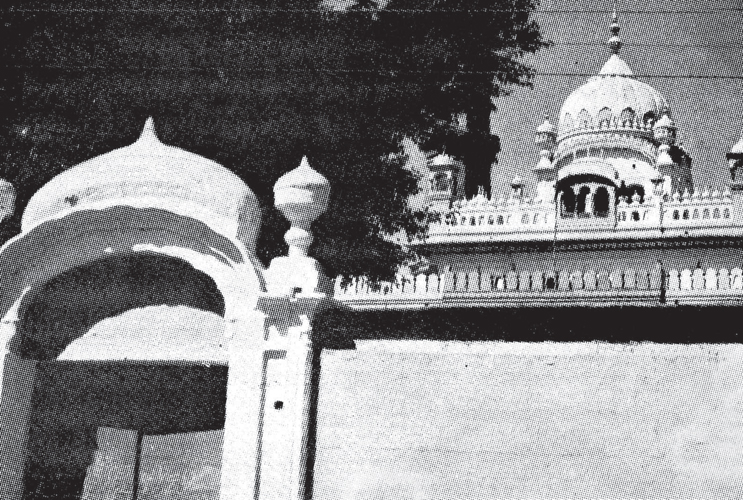

The first question arises out of our characteristic perceptions of a tradi¬tional environment such as the old walled city of Lahore, which provides the illustrations for this article. We are attracted, of course, to the great monuments of Mughal and Sikh rul¬ers – broadly accepted architectural masterpieces. Proceeding into the bazaars, we respond positively to their “human scale” and pedestrian character, their vitality, colour, and the strong interplay of light and shade; to the craftsmanship evident in many articles displayed for sale : saris, gold embroidery and brocades, jewel¬lery, copper vessels; to the smells of the spice bazaars. In the residential mohallahs opening off the bazaars, we are struck by the comparative quietude and privacy, and by the fine architectural details of older houses. These reactions are primarily sensual and aesthetic, reflecting our profes¬sional training. The writings of Cullen, Bacon, Rudofsky and Mumford come to mind. Our negative responses to multimodal traffic density and confu¬sion, to the many dilapidated buildings and katcha hutments, to lack of space, to commercial encroachments which mask fine old facades, and to frequent¬ly filthy streets-these are also aesthetic, but probably born as much out of our own different personal circumstances as our heightened visual sensitivity. Few urban designer make their homes in traditional areas of the city.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|