Environment & Ecology

Between Ages of Ice | Rhea Shah

LA 60 |

|

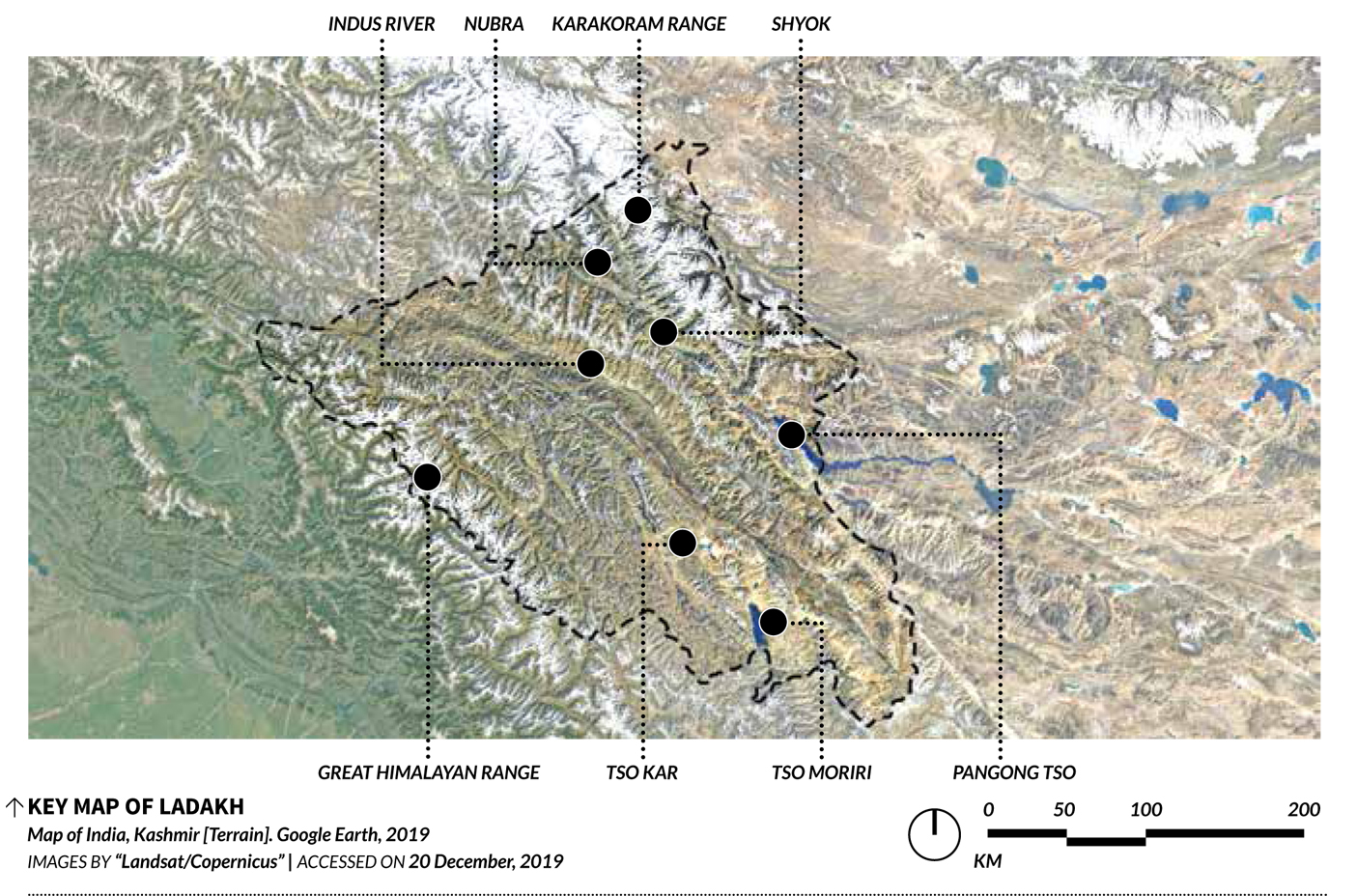

Ladakh: A history of a desert waterscape

Today, the Ladakhi waterscape sees major geological changes, such as the melting of long frozen glaciers and rising water levels, spurred by global climate change. The Ladakhi ecological and cultural spheres are a storehouse of techniques to preserve the environment and have modernised themselves to remain relevant even in these times. There is much to be learnt from them, especially how to make the most of local resources and not jeopardise their very existence.

|

|

|

|

Crafted by the immeasurable power of time, Ladakh is an epitome of

glacial speeds. The history and future of Ladakh lies in the slow changes between ages of ice. Over the last 200 million years, the Indian Plate has been hurtling toward the Eurasian Plate. About 50 million years ago, the Himalayas began to emerge as a consequence of their dramatic crash. The oceanic crust of the Indian Plate slipped below the Eurasian Plate, forming the Indus Suture; like the skin of the earth folding, wrinkling, writhing to accommodate the convergence and uplift of the two muscular tectonic masses. In what can only be described as mythical in human time, the floor of

the Tethys Ocean, once deeply submerged, was pushed up to +3000 m above sea level to become the highest plateau of the world.Ladakh lies exactly above the Karakoram fault line, amidst dynamic formations of rock, that still shift and move with the plates.

An accumulation of magma, resulting from the clashing of plates, generates immense heat that rises close to the surface in Ladakh as hydrothermal energy. This thermal heating of the Tibetan Plateau creates the pressure differential essential to the flow of life-giving monsoon winds. Snows melt,feeding silt-carrying rivers that transform the sun-scorched plains of the subcontinent to verdure. Ladakh is also a pause in the trans-continental, thermodynamic multi-state flow of living waters. As a waterscape, Ladakh supports billions of lives across the densely populated and diverse Indian subcontinent, in addition to its own population.

Situated in the rain shadow of the Great Himalayan Range, which lies to the south, Ladakh is in essence a desert, with annual precipitation between 93 mm [Leh] and 250 mm [Zanskar]. The valley prospers despite its harsh environment, fed by approximately 1,00,000 square kilometers of melting glacier ice, carefully held water and flows of people. Ancient serais along the Silk Route, made passable by the freezing glaciers and gentler winter waters of the Shayok river, carried from Leh amongst other precious goods, red coral to Kashmir and beyond, serving as a cultural remembrance of the

oceanic waves that once ebbed and flowed through the landscape.

Coral glimmers in sun and snow worn skin as elderly Ladakhi herders

drive their cattle through the grasslands formed by the melting

snow cover. The same spring-born glacial-melt waters the terraced

fields of the valley, through a series of well crafted irrigation channels that sustain life, as they have over thousands of years. Pastoralists trace the melting snow in the form of grass, across landscapes littered by glacial debris. Practices in traditional Ladakhi culture reflect the imagination of a continuous human, animal, environment, divine existence. The elderly in Ladakh are loathe to give up their herds even as they can no longer tend to them. Retreating glaciers, floods and other calamities are seen as retribution from forgotten natural deities. Stories of ancient attempts to resurrect the glaciers abound amongst the older generations, of villages coming together to tend to ice holding walls in warmer years.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|